The word culture has extensive applications in its sense. The culture so far as India is concerned is composite. Buddhism which moulded Indian thoughts for several centuries contributed largely to Indian culture in its various aspects.

The contribution that Buddhism made to the cultural advancement of India is indeed notable. The part played by the viharas (monasteries) and sangha (order) was unique in this regard; in this paper, an attempt has been made to describe some of its important aspects, such as culture, social ideals and political, educational system, language, literature and artistic development based on the aesthetic ideals acquired by the people of ancient India. Buddhism in India.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is the definition of Culture?

- Social Ideal

- Political Ideal

- Literature & Language

- Education System

- Art and Architecture

- Buddhist Music

- Conclusion

- References:

- Other Important Posts

Introduction

Buddhism greatly influences the Indian religion. It gave to Indian people a simple and popular religion. It rejected ritualism scarifies and the dominance of the priestly class. It has also left its permanent mark on Indian religious thought.

Buddhism appealed to the masses on account of its simplicity, use of vernacular language in its scriptures and teachings and monastic order. Buddhism left a deep impact on society. It gave a serious impetus to the democratic spirit and social equality. It opened the doors to women and Shudras.

Buddhism encouraged the abolition of distinctions in society and strengthened the principle of social equality. Culture and religion concern and deal with some similar human issues in terms of the concept of values, the way of thinking, inner feelings and the method of expressing by means of symbolism.

Buddhism in particular, as a spiritual community (Sangha), was quite different from the Christian churches with their centralized organizations and hierarchical structures. Sanghas in other countries were never subordinated to the Sangha in India.

This feature gives Buddhism its authenticity and enables those various local talents to express themselves maintaining the essence of the Dharma. While spreading Buddhism not only assimilated into the local culture but also acted as a connector between east and west. Culture includes all areas such as literature, music, dance, drama, printing, painting, architecture and art associated with Buddhism.

This mainly focuses on literature, architecture and music, and will be divided into five points. The first point will examine the definition of culture.

The second point will explore the contribution to Social change in Indian society. The third point will show the impact on literature and languages. The fourth point will look into the contributions to the Education system in India. The fifth point will explore the contribution to Art, Architecture and music by Buddhism.

What is the definition of Culture?

The definition of culture is the system of shared beliefs, values, customs, behaviors, and artifacts that the members of society use to cope with their world and with one another, which are transmitted from generation to generation through learning.

This definition points to four important characteristics stressed by cultural relativism, symbolic, composition, systematic patterning, learned transmission and societal grounding.

Culture, as a body of learned behaviors common to a given human society, acts rather like a template shaping behavior and consciousness within a human society from generation to generation. So culture resides in all learned behavior and in some shaping template or consciousness prior to behavior as well (that is, a “cultural template” can be in place prior to the birth of an individual)

Robert Bellah defines religion as a set of symbolic forms and acts that related humans to the ultimate conditions of their existence. Hall, Pilgrim and Cavanagh give this definition: “Religion is the varied, symbolic expression of, and appropriate response to that which people deliberately affirm as being of unrestricted value for them”.

Theoretically, both culture and religion concern and deal with some similar issues of humanity such as the concept of value, the way of thinking, empirical feeling and the method of expression. In order to present the significance of art and religion, symbolism is a meaningful means.

Therefore, the relationship and reciprocity between culture and religion, Buddhism in particular, are inevitable. The Buddhist Sangha was quite different from the Christian churches with their centralized organizations and hierarchical structures.

Sanghas in other countries were never subordinated to the Sangha in India, a fact equally valid and applicable to the offshoots of the Theravada tradition and of the communities that were inspired by the Mahayanist and Trantic traditions.

Social Ideal

Buddhism brought a new outlook in the social life of ancient India. Before the rise of Buddhism, there was the Vanna (grade) which mainly determined the various grades in society. According to Rhys Davids the rigid caste system that we know of today was not in vogue at the time of Buddha but was in the making then.

The Pali texts speak of the division of society into four castes. Viz. Khattiya, Brahmana, Vessa and Sudda. An adequate idea about the lofty claims of the Brahmins can also be gathered from them. They maintain that the Brahmins alone form the superior class, all other classes being black, that purity resides in the Brahmanas alone and not in non-Brahmanas and that Brahmans are Brahma’s only legitimate sons, born from the mouth, offspring of his, and his heirs’.

But Buddha’s attitude towards the division of society on the basis of caste was all along antagonistic. He denounces the superiority of the Brahmins on the ground of birth.

The Vasala and Vesettha Suttas of the Suttanipata, the Madhura, Assalyana and Canki Sutta of the Majjhimankikaya prove the worthlessness of the castes Buddha did away with all social distinctions between man and man and achieved social justice thereby.

From the Cullavagga we find that, “just as the great rivers, such as, the Ganga, the Yammuna, the Aciravati, the Sarabhu and the Mahi, when they pour their waters into the great ocean, lose their names and origins and become the great ocean, precisely so, you monks, do these four castes the Khattiya, the Brahman the Vessa and Sudda when they pass, according to the ‘doctrine and discipline of the Tathagata, from home to homelessness, lose their names and origins.”

Buddha thus stood for the equality of castes.

He maintained that it was Kamma (action) that determined the low and high state of a being. By birth one does not become an outcast, by birth one does not become a Brahmin. Every living being had Kamma (action) as its master, its kinsman, and its refuge.

We also find that the equality of social position based on actions (Kamma) and not on birth so much insisted on by Buddha was also in later times emphasized by the saints, such as Ramananda, Caitanya, Kabira and others. There was no distinction of caste in the sangha. Buddha’s disciples belonged to all strata of society.

For instance, we know that Upali who was a barber by caste occupied an important position in the Sangha. Admission to the sangha was open to men and women alike. We are told that Buddha was at first unwilling to admit women into his sangha.

But at the insistence of his foster mother Mahapajapati Gotami agreed to admit women into his sangha. He did away with the religious disabilities of women. Womanhood was no bar to the attainment or Arhathood, the goal of life. A new and respectable career was opened before women.

This attracted a number of women who attained positions of eminence in the various spheres. The Therigatha gives us names of eminent nuns. Buddha thus raised the status and position of women in the society. Truth (sacca), righteousness (dhamma), charity (dana), non-violence (asahsa) and the like were further the important norms that Buddha had postulated for the society.

Buddhism gave the greatest jolt to orthodox Brahmanism. Buddhism exercised profound influence in shaping the various aspects of Indian society. It developed a popular religion without any complicated, elaborate and unintelligible rituals requiring necessarily a priestly class. This was one of the reasons for its mass appeal. The ethical code of Buddhism was also simpler based on charity, purity, self sacrifice, and truthfulness and control over passions.

It laid great emphasis on love, equality and nonviolence. It became an article of faith for the followers of Buddhism. It laid emphasis on the fact that man himself is the architect of his own destiny. It was devoid of any elaborate idea of God. Although Buddhism could never dislodge Brahmanism from its high position. It certainly jolted it and inspired institutional changes in Indian society. Rejection of the caste system and its evils including rituals based on animal sacrifices, conservation, fasting and pilgrimage, preached total equality.

The promotion of social equality and social justice helped Buddhism to cross the frontiers of Indian sub-continent and became a world religion. In the field of education, Buddhism tried to make education practical, action-oriented and geared towards social welfare. Most of the ancient Indian universities like Nalanda, Taxila were products of Buddhism.

Political Ideal

Buddha lived in the 6th century B.C. It was an age of great upsurge, intellectual and social, in many parts of the world. In India too we also notice the upheaval in the domain of political and social ideals, educational system and the like Gautam Buddha was born in a famous Sakya clan.

His father Suddhodana with his capital at Kapilavastthu was the chieftain of the clan which had an oligarchic system of government. There were other neighboring clans, viz. the Vajjis, Licchavis, Koliyas, Videshas and the like. They had also republican peoples. Being disgusted with the earthly pleasures Gautama in his youth left home and adopted the life of a recluse to rescue mortal beings from the miseries of the world.

After his enlightenment, he started his missionary career at the age of thirty-five and continued it for forty-five years, i.e. till his Mahaparinibbana. With his sixty disciples, Buddha started his religious order, known as the sangha, which contributed much to the propagation and popularity of Buddhism and exists even today.

From the Mahavagga we learn that he sent them out in different directions with the words, “Go ye, now oh Bhikkhus, and wonder, for the gain of the many, for the welfare of the many, out of compassion for the world.

Let not two of you go the same way. Preach the doctrine which is glorious in the beginning, middle, and end, in the spirit and in the letter, proclaim a consummate, perfect and pure life of holiness” Ere long the member of his disciples had grown fairly large and he had to work out rules and regulations for the guidance of the members of the sangha (order) which are contained in the Vinayapitaka.

The sangha (order) which Buddha founded was not, of course, a new one. At and before the rise of Buddhism there were forms of communal life, but they lacked any organization and code of rules regulating the life of the members. Buddha’s credit lay in his thorough and systematic character which he gave to the sangha (order).

As already observed, Buddha was born in a republican state. He was imbued with democratic ideas from his boyhood. The political constitution of the clans from which many men joined the sangha as Bhikkus (monks) in early times was further of a republican type. One can, therefore, naturally expect Buddha’s democratic ideals in the constitution of the Sangha.

Lastly, the democratic ideal was further developed and materialized in the field of state administration by the Maurya emperor Asoka who was indebted for this grand and noble ideal to Buddhism. His ideal of Dharmavijaya was not only a missionary movement but a definite imperial policy.

It indeed achieved the ideal of unity and fraternity for the people of India. Buddhism has contributed significantly to the development of the forms and institutions of civil government, including the ideals of kingship, in ancient India. Sakyamuni was a teacher also of the principles of righteous government, individual freedom and the rule of law.

The seven conditions of stability of a republican body which he suggested to the Magadhan diplomat, Vassakara, are words of social wisdom still relevant to our contemporary political life.

Literature & Language

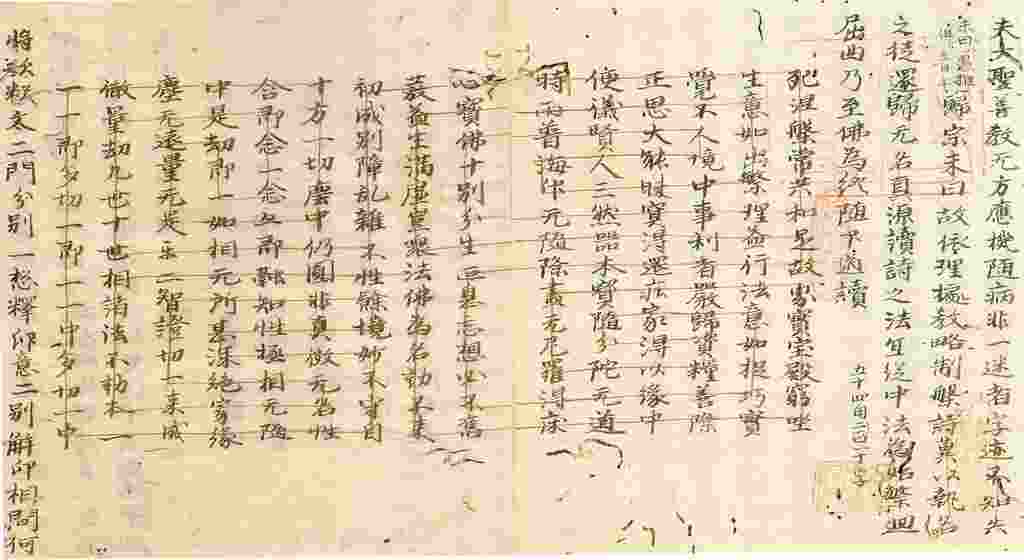

Buddhist contribution to Indian languages and literature was matched only by the richness and variety of the Buddhist religion and philosophy. The development of Pali and its literature was wholly due to Buddhism of its great historical, cultural and literary value, which scholars are well aware of. But Pali was not the only area that contributed to the flowering of the Buddhist tradition.

The vast amount of Pali texts, canonical and non-canonical, is the contribution of only one major branch, doubtless one of the most ancient and orthodox branches of Buddhism. Several other schools of Buddhism cultivated varieties of Buddhist Sanskrit and varieties of Buddhist Prakrit.

The Buddhist intellectuals of ancient India contributed not only to what is now called Buddhist Sanskrit and its varieties but also to what is called Classical Sanskrit. Thus, while we have the Avadana and Mahayanasutra in a Sanskrit peculiar to the Buddhist tradition, we also have such texts as the Mahayamakashastra, the Jatakamala and the Tattvasamgraha to mention only three out of numerous texts, in classical Sanskrit.

The Sanskrit of the Buddhist tantras and sadhanas presents yet another category of language. Then the language of the epigraphs of Ashoka is kind of Prakrit, by no means uniform in all versions of the major rock edicts, quite different from the language of what has been called the Gandhari Dharmapada.

The Buddha’s injunction to his disciples to learn the sacred word in their own languages (sakaya–niruttiya) was fully carried out by the faithful Buddhist.

The Pali Tripitka covers nine classes of literary forms, that are the Buddha’s teachings (sutras), rhythmic verses (geyas), prophecies (vyakaranas), chants or poems (gathas), impromptu or unsolicited addresses (udanas), narratives (ityuktas or itivrttaks), stories of former lives of Buddha (jatakas), expanded sutras (vaipulyas) and miracles (adbhuta–dharamas).

The Mahayana Canon includes twelve divisions, cause and condition (nidana), commentary (adhidharma) and analogy (avadana) other than above nine. The Buddhist Tripitaka presented and provided abundant literary genres from Indian early Buddhism to nowadays.

Among them, the Vimalakirtinirdesasutra, the Sadharma–pundarikasutra and the Surajgamasamadhisutra are well-known literary works. The Sutra of the one Hundred Parables, translated into various languages, was honored as unique literacy work.

The Raktavitisutra is a combination of many small sutras. The Lalitavistarsutra is long story. The Suratapariprcchasutra is fiction. The Visesacintabrahmaparprcchsutra is literary work – half fiction and half dharma. The Jataka from which several stories have found their way to Aesop’s Fables and Arabian Nights are stories from the Buddha’s previous lives.

In addition, Theragatha and Therigatha are ethical teachings taught in verses. One of the latest contributions made by the Buddhists to the literature of India was in the form of dohas or gitis (songs) composed by Buddhist Siddhas (adepts in Tantrika culture) in Apabhramsha.

This language seems to have been the mother of several modern Indian languages including Hindi, Oriya and Bengali. The terms and concepts of Buddhism were transmitted by Siddhas through the medium of their Apabhramsha poems to mediaeval lore of saint poets.

Unfortunately, only a small portion of the Siddha literature has survived to this day. Finally, mention may be made in passing of the impact of Buddhist writers on Sanskrit grammar and lexicography. A Buddhist scholar named Sarvavarma wrote the Katantra, in which he tried to build a new system of Sanskrit grammar. He possibly lived in or about the second century CE.

In the eight century, a commentary was written on Katantra by one Durgasimha. The Buddhist scholar, Candragomin (500CE) wrote the Candravyakarana with an auto-commentary (vritti) on it. It became the standard grammatical treatise in most Buddhist countries of Asia.

Education System

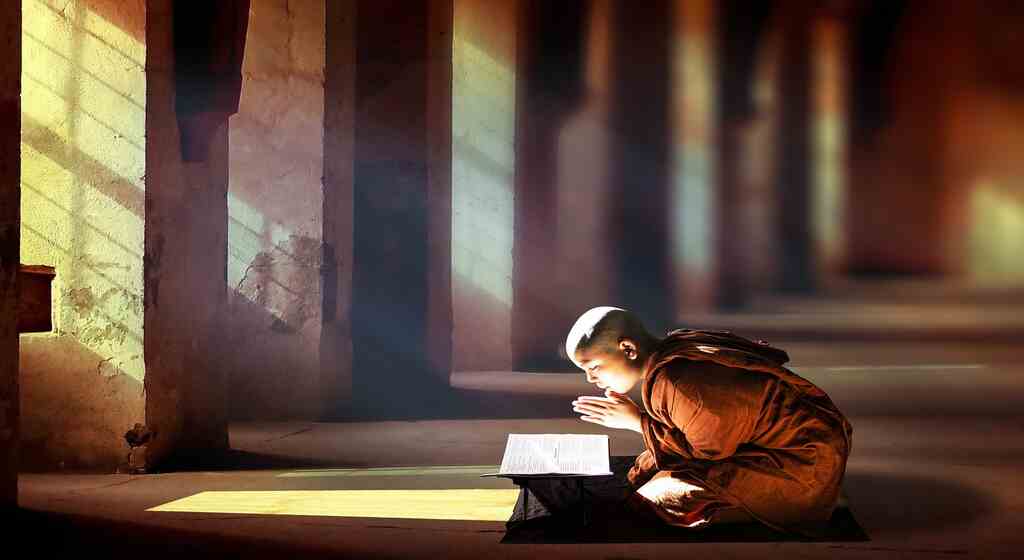

When the Buddha had founded at Varanasi the ideal sangha consisting of sixty worthies (arahants) he commanded them in the following words: “Walk, monks, on your tour for the blessing of many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the welfare, the blessing, the happiness of deva and men.

Monks, teach Dhamma which is a blessing in the beginning, a blessing in the middle, a blessing in the end” We quote this passage from the Mahavagga to recall that Buddhism was, from the very beginning, a missionary movement founded on compassion, determined spiritually to transform the world of humanity and to awaken in morally, intellectually and spiritually.

Who can say how many millions of human beings had been awakened morally, intellectually, and spiritually by the message of Buddhism in the course of its long history?

We can only imagine that an immeasurable multitude of creatures must have been awakened in India alone. Buddhist monastic colleges and universities of ancient India threw open their doors to all those who wished to know, irrespective of caste, color, creed, or country.

The introduction, expansion and proper management of the educational system are one of the main functions of the modern state. In ancient times the Christian missionaries in Europe and the various religious orders in India planned out their own educational methods.

They also received the active support and patronage of the ruling powers and the nobility in this regard. Among them, the Brahminical system of education s the most ancient. It has been in vogue even today since the Vedic age. The tradition of the system of education with which we are concerned here relates to the Buddhist system of education only. It differs from the Brahmanical system in some aspects.

There is no denying the fact that in ancient India all education that was imparted could broadly be divided into religious and secular. Religious education, of course,out-numbering the secular one. With the origin and development of the Buddhist sangha, came into existence the system of education which was monastic in conception.

The Buddhist vihara (monasteries) were the centers of education and the monks imparted instructions on both religious and secular matters. The history of the Buddhist system of education is really the history of the Buddhist Sangha.

The viharas (monasteries) took up the teaching work not only for the monks but also for other seekers after knowledge from outside. It was, therefore, ‘organizes on the ideals a residential university for the monastic members only and appeared as a day school for the laity, and its teachers were selected from those monks who were highly cultured, experienced and educated’?

In the viharas (monasteries) various branches of knowledge were taught. But the emphasis was generally on matters of religion (Dhamma) and rules of discipline (Vinaya).

From the Cullavagga we learn that those who wanted to specialize in some subjects were taught by experts of those subjects. The teachers of allied subjects were given seats close to one another. It further gives the names of subjects that were taught in the viharas (monasteries).

A Jataka tells us that king Pasendai begins defeated by Ajatsattu approached the monks and learnt the method of forming a battle array from them and ultimately defeated Ajatasattu.

From the Milindpanha we learned that constructing and repairing buildings and the like were also taught in the avasas (monasteries). The viharas (monasteries), as already observed, were the residential center of learning. They came into existence first for spiritual training for the monks. But they gradually changed into great centres of learning. Later on, they turned into big universities to which flocked students far and near to gather knowledge on different subjects.

Admission to them was thrown open not only to monks but also to others who had a desire to received education there from. Kings, nobles and the like used to meet the cost of running these universities. Students in no way felt any inconvenience to prosecute their studies there.

Teaching of various subjects was carried on uninterruptedly from morning to evening. Of them the University of Nalanda to which flocked students from far-off countries attracts our attention most. It accommodated ten thousand pupils and one hundred teachers were there to teach them. During this period there were other universities like Vallabhi, Vikramasila, Jagaddal and Odantapuri which deserve mention here.

This shows the vastness of cultural activities carried on in the domain of education by the monks of the viharas (monasteries). Lastly, it will not be out of place to mention here that Kaviguru Rabindranath Tagore who noted for his great love for Buddhism built to up his Visvabhrati on the model of the Buddhist viharas (monasteries) which were great centre of learning in those days.

Art and Architecture

Art is the product of both feelings and wisdom. Cultures are associated with art. Buddhism supports art with its profound philosophy. Lengthy history and rich culture. In fact, Buddhism itself is a treasure of art. The influence of Buddhism on art has been manifold, so that we find examples that are not limited to spiritual themes. During the past 2,000 years, Buddhism influenced eight traditional arts, crafts and calligraphy as well.

The achievement of art made by Buddhism is a unique treasure for all human beings throughout the world. Architecture is a visual representation of culture. Through architecture, one can understand a certain culture’s environment, climate, societal priorities, characteristics, and dynamics of human interaction, customs, beliefs and living habits as well as the relationships among these qualities.

The beliefs and spiritual traditions of a culture cannot be separated from architecture. Buddhist architecture emphasizes monasteries, stupas and caves. Even if we judge him only by his posthumous effects on the civilization of India, Sakyamuni Buddha was certainly the greatest man to have been born in India, and the contribution of his teaching towards Indian history and culture was perhaps greater than that of Brahmanism.

Before becoming a major faith and a civilizing force in the world, Buddhism had been a mighty stream of though and a tremendous fountain-head of human culture in its homeland. Ignorance or neglect of the available Buddhist literature is not the only shortcoming of the “traditional approach.

The fact that the knowledge of Indian archaeology is confined to a handful of scholars is another factor which has prevented most of us from viewing Buddhism in its entirety. Mortimer Wheeler observes that “Archaeologically at least we cannot treat Buddhism merely as a heresy against a prevailing and fundamental Brahmanical orthodoxy.

For, in spite of the ravages of time and destruction by Indian foreign fanatics, Buddhism is still speaking vividly and majestically through its thousand of inscriptions, about one thousand rock cut sanctuaries and monasteries, thousand of ruined stupas and monastic establishments and an incalculable number of icons, sculpture, paintings and emblems, that it prevailed universally among the classes and masses of India for over fifteen centuries after the age of the Buddha, and that its ideas of compassion, peace, love, benevolence, rationalism, spiritualism and renunciation had formed the core of the superstructure of ancient India though and culture.

Buddhist art owes its origin due to the religious devotion and fervor of Buddha’s followers. But it received the greatest incentive from the great Maurya emperor Asoka through whose efforts Buddhism became a popular religion in India.

He did all that was possible for the propagation of Buddhism and art which reflects ‘the ideas and ideals, ambitions, joys and fears of Buddhist laity.’ There were other lay devotees who generously contributed to the erection of caityas, stupas and the like to express their deep veneration to Buddha.

Thus the inspiration of the Buddhist art came from religion. Indeed, it also served as a valuable means for the propagation of Buddhism. Starting from the time of Emperor Asoka up to the middle of the 1st century B.C. Buddha was represented by a few symbols.

We do not come across any image of Buddha. The followers of Buddha did not believe in the worship of the image then. They paid their veneration to the symbols. We thus see that a garden with trees in the midst and his mother represents his birth, a house his renunciation, the Bodhi tree his enlightenment, his first discourse to his Pancavaggiya bhikkhus by a sheel flanked by a deer and the like, these kinds of symbols are found at Sarnatha, Nalanda, and Amaravati.

Stupas were also erected over the relics of Buddha, specimens of which are to be found at Sarnatha and Amaravati. Next comes pictorials representation of the Jataka episodes depicting the previous lives of Buddha.

In the bas-reliefs of Bharhut and Sanchi we find this kind of representation. During this period Asoka built large pillars at important places throughout India. His famous Lion Capital Pillar is indeed one of the noblest products of Buddhist art. It has been accepted as the national emblem of free India. This period also witnessed the appearance of rock-cut temples at Bhaja, Karle and Ajanta.

The first representation of Buddha in anthropomorphic form in sculptures dates from the 1st century A.D. Buddhist art received a great impetus during the reign of the Indo-Greek and Indo Scythion rulers. King Kaniska who played the part of second Asoka was a great lover of art. He patronized the artists to curve statues of Bodhisttvas and Buddhas to popularize Buddhism.

As consequence, statues of Bodhisattvas and Buddhas. In various postures (mudras) were produced and they were in great demand. Mathura became shortly a great centre of Buddhist art. Many Buddhist stupas, caityas, viharas were constructed during the reign of Kaniska. Here is a pertinent question about the origin of the Buddha image.

Opinions differ as to its origin. Some scholars hold that the image of Buddha was first made in the Gandhara school of art while some others hold that it was the Mathura schools which was responsible for the first image of Buddha. We do not like to enter into a polemic here we keep the question open.

The Mathura art reached its apex in the Gupta period. The Gupta age was an era of art. It brought the Buddhist art of India to its highest perfection as an expression of the inner feelings of devotion and zeal of the artists. Lastly, Buddhist art like Buddha’s religion was not confined to its land of origin. Along with Buddhism it spread to the north south and south-east of India and made its influence felt in those regions.

The full flowering of Buddhist art can be notice in the temple of Borobodhur in Java, which can be regarded as ‘the architectural wonders of the world’, and ‘nowhere in the world has the Buddha Pratima or the hand of the stone sculptor revealed the quality of spiritual beauty so characteristic of the Dharma’.

The same may be said of the Buddhist monuments of Chandi Kalasan and Chandi Mendut in Java as also of the temple of Bayan in Ankor Thom (Cambodia). Thus the achievement of Buddhism in the realm of art is most significant and also unique in all respects.

Buddhist Music

Music is the world’s common language reaching far and wide unrestricted by time, space, political boundaries, ethnicity, or tradition. It expresses the emotions of the human spirit. A song or a sincere praise to the Buddha can often raise the human spirit to a sacred realm. Music plays a very important role in spreading Buddhism.

In Buddhism, music is one form of offering amongst many and an important part of Buddhist cultivation. In order to express devotion. Buddhist chant praises to Buddhas and bodhisattvas, gaining limitless merits in the process.

The Saddharmapundrikasutra indicates that, “With a joyful heart, we chant the merit of the Buddha, even with just a few short notes, all can attain Buddhahood”. In order to promote Buddhism, sutra recitation, chanting and lecture are usually advocated. Among them, sutra recitation and chanting are called Buddhist music.

Buddhist music originated from the age of the Vedas in ancient India. It was popular to chant sutras and gaths, the practice of which was one of the five branches of the great classical studies of India concerning sound and music. During the Buddha’s time, chanting was employed as a skillful means to spread the Dharma. The teachings were expressed in verses or gathas which were passed on through chanting.

This practice made it easy for disciples to remember and recite. Monks were especially encouraged to conduct or compose music for chanting. During the time of King Asoka, Buddhist music was played with musical instruments made of leather, shells and so forth. During the second century CE, Asvaghosa composed the Praise for the Buddha based on the life and times of Sakyamuni Buddha. He later rewrote it as a play, Rastrapala, which was performed in the City of Pataliputra.

As a result, many people were moved to become followers of the Triple Gem. During the sixth and seventh centuries CE, King Siladitya supported his leadership by using Buddhist music in order to give the people peace. Buddhist chanting is today an important part of practice in any Dharma function – making praise, offering’s cultivation, teaching liturgies. The profundity, sacred pursuits and compassion and wisdom of Buddhism are clearly expressed through music.

Over the past two thousand years, Chinese Buddhist music had developed into many schools and traditions delineated by geographical regions or practices. It has integrated with the music of the common folk, the imperial court and other spiritual tradition, each influencing one another and developing together. This long history of its development and the process of its inheritance have made Chinese Buddhist music invaluable and impressive.

Conclusion

The Buddhist Viharas were used for education purposes. Nalanda, Vikramshila, Tasila, Udyantputi, Vallabhi and others cities developed as high Buddhist learning centres. Buddhism helped in the growth of literature in the popular language of the people. The literature written both in Pali and Sanskrit were enriched by scholars of Theravada and Mahayana sects. The Buddhist texts like Tripitakas, Jatata, Buddha charits, Mahavibhasa, Milind panho, Lalit Vistara are assets to Indian literature.

The main contribution of Buddhist culture to India life in the domain of architecture, sculpture and painting. The stupas, viharas, chaityas that were built at Sanchi, Bahrut, Bodhgaya, Nalanda, Amravati, Taxila and other places are simply remarkable. The Sanchi Stupa with its beautiful ornamental torahs in considered a masterpiece in architecture.

The cave temples of Ajanta, Karle, Bhaja, Ellora etc show their achievement in rock cut cave temples. The Ajanta painting depicting touching scenes of Buddha’s life are world famous. They fostered a new awareness in the field of culture.

Buddhism established intimate contact between India and foreign countries. Indian monks and scholars carried the gospel of Buddhism to foreign countries from the 3rd century BC onwards and made it the prominent religion of Asia. These religious movements helped in carrying the message of Indian civilization to many distant countries of Asia. It also helped in assimilating foreign influence in Indian culture.

References:

- Ambedkar, B.R., The Buddha and His Dhamma, Buddha Bhoomi Publication, Nagpur, 1997.

- Bapat, P.Y., 2500 Years of Buddhism, Ministry of Information, Government of India, New Delhi, 1959.

- Brown, Percy. Indian Architecture. Bombay: Taraporevala and co., 1959.

- Dhammika, Shravasti Ven. The Edicts of King Ashoka. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society,

- Gombrich, Theravada Buddhism, 2nd edn, Routledge, London, 2006,

- Harvey, Introduction to Buddhism, Cambridge University Press, 1990

- Herbert J. Gans Popular Cultural and High Culture: An Analysis and Evaluation of Taste: Yunchen Industry Co., Taipei, 1985.

- Jayadeva Singha, An introduction to Madhyamaka Philosophy, Motilalbanarisidass, Delhi, 1997.

- Jones, J. J. Mahavastu. England: Pali Text Society, 1952.

- Joshi, L.M. Social Perspective of Buddhist Soteriology” in Religion and Society, Vol. VIII, No.3, Bangalore, 1971.

- Joshi, L.M., Studies in the Buddhist Culture of India, Motilal Banarasidass, Delhi, 1967.

- Kashyap, Jagdish, Therigatha, Nav Nalanda Mahavihar, Nalanda, 1958.

- Kousalyayan, Bhadant Anand, Jataka, Vol.1-VI, Hindi Sahitya Sammelan Prayag, 1995.

- Lord Chalmers Ed., Buddha’s Teachings Being The Sutta-Nipata or Discourse-Collection, Motilal Banarasidas Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, 1997.

- Meshram, Manish, Bouddh Darshan ka Udbhava evam Vikas, Kalpana Prakashak, Delhi, 2013.

- Michell, George. The Penguin guide to the monuments of India, Vol I. London: Viking, 1989.

- Morris, R. and Hardy E. ed. Anguttaranikaya Vol. 111, P. T. S. London, 1900.

- Narada, Mahathera. A Manual of Buddhism. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Buddhist Missionary Society, 1992.

- Oldenberg, Hermonn ed. Vinaya Pitaka. Vol. 4. P. T. S. London. 1984.

- Rinpoche, Thrangu.. A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life of Shantideva: A Commentary. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, 2002.

- Samyuttanikaya Vol.II, Nalanda Devanagari Edition

- Shastri Dvarkadas, Digha Nikaya, Vol.1-3, Bouddh Bhartiya Prakashan, Varanasi, 1996.

- Shastri, Dvarkadas, Samyuktt Nikay, Vol.1-IV, Bouddha Bharatiya Prakashan, Varanasi, 2000.

- Sri Dhammananda Ed. & Tr, The Dhammapada, The Corporate Body of the Buddha Educational Foundation, Taiwan, 2006.

- Tadgell, Christopher. The History of Architecture in India. London: Phaidon Press, 1990.

- Upadhyaya, B. S., Pāli Sāhitya Kā Itihāsa, Hindi Sāhitya Sammelana,Prayāga, Delhi,1994.

- Vimalkirati, Therigatha, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2003.

- Warder, A.K. Indian Buddhism, Motilal Banarasidass, Delhi. 1971.

- Winternitx, M., History of Indian Literature Vol.III, Delhi.

Who is author of this?

I am genuinely grateful to the owner of this site who has shared this impressive piece of

writing at here.

Your style is very unique compared to other folks I have read

stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I’ll just book

mark this site.

What’s up friends, its fantastic post on the topic of educationand fully explained, keep it up all the time.

Perhaps I agree with your phrase

Magnificent items from you, man. I have be mindful your stuff prior

to and you are simply too fantastic. I really like what you have acquired here, really like

what you are saying and the way in which through which you

are saying it. You’re making it entertaining and you still

care for to stay it smart. I can’t wait to learn much more from you.

That is really a terrific site.

Thanks for any other informative site. The place else may just I am getting that type of information written in such an ideal means?

I have a project that I am simply now running on, and I have

been at the glance out for such info.

Your style is so unique in comparison to other

people I have read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you’ve got the

opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark this web site.

I am regular reader, how are you everybody? This article posted at this web page is genuinely good.

I blog frequently and I really appreciate your information. Your article has really peaked

my interest. I will book mark your blog and keep

checking for new details about once per week.

I subscribed to your Feed as well.